Developer: Galactic Cafe

Publisher: Galactic Cafe

Platform(s): PC

Price: £12

Please stop reading this review immediately.

You didn’t. Alright, well. That’s The Stanley Parable, in essence. It’s a game about choice, but also a game about not really having any at all. It’s a game about being told to do something and either going along with it or choosing to disregard it and try something else, but always only having a limited number of options.

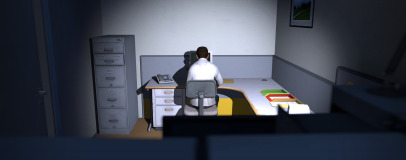

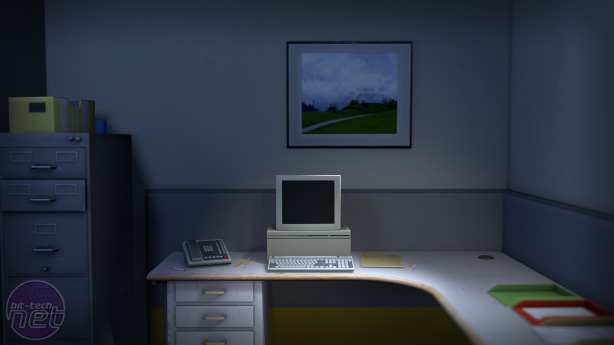

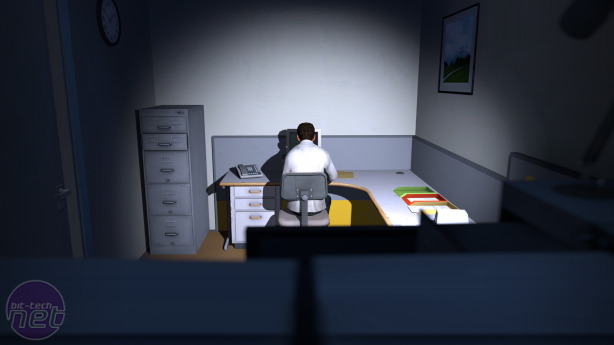

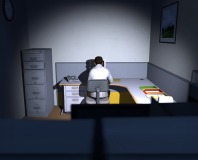

The titular Stanley is an office worker tasked solely with pressing a key on a keyboard as he’s instructed. One day the commands unexpectedly stop. You guide him through his building to find out why and discover that everyone around has suddenly disappeared without explanation. Not only this, but many of his actions are now preceded by a golden voiced narrator offering a suggestion of not only what he should do, but also a reaction to what he has actually done.

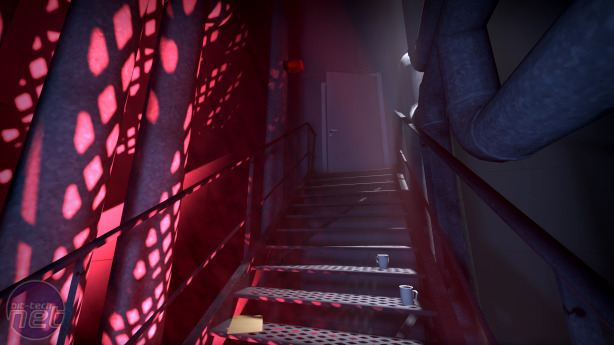

The Stanley Parable began as a free mod for Valve’s Half Life 2, and it wore that quite proudly, with deliberate references to the series in the form of wholesale reusing textures, assets and even entire map sections. It's still available to download for free, but this full game serves as an extension of the same idea, polished to a pristine shine with far better textures and level design, with some of the initial choices carried over and many new ones added.

Your earliest decision is to pick between two doors. The narrator suggests that you go left, doing so carries on the story without any hiccup until the next choice, disobeying means a brief attempt to get you back on track, but continuing to do so can lead to entirely unique outcomes.

Some of these branches are more extensive than others, some leading to elongated sections of unique gameplay, others offering further branching options. Though following the story as described by the narrator results in a narrative that is sewn up with a tidy bow, more interesting ideas emerge through different choices. The game starts to make huge statements about factors that weigh into modern game design like hand-holding, following a critical path without any player agency, extensive playtesting sessions, the issue of creating a game solely with the intent that it be enjoyed by an audience, along with scathing critiques of both overly pretentious art-first-design-later creation and unnecessary social integration.

A great deal of this feels clever, it avoids the common pitfall that games with a message about gaming fall into where their commentary on the ridiculousness of a trope is to simply repeat the trope and call attention to it, here each idea is taken to a ridiculous extreme, examined, then argued.

Though some playthroughs benefit from relying on continued repetition of the first few rooms, it can be tiresome wandering the same path hearing the same dialogue again in an attempt to reach the next ending. There’s no real way to combat this, the parts where this revisiting serves the narrative require it, but the sections which don’t unfortunately suffer for it.

Publisher: Galactic Cafe

Platform(s): PC

Price: £12

Please stop reading this review immediately.

You didn’t. Alright, well. That’s The Stanley Parable, in essence. It’s a game about choice, but also a game about not really having any at all. It’s a game about being told to do something and either going along with it or choosing to disregard it and try something else, but always only having a limited number of options.

The titular Stanley is an office worker tasked solely with pressing a key on a keyboard as he’s instructed. One day the commands unexpectedly stop. You guide him through his building to find out why and discover that everyone around has suddenly disappeared without explanation. Not only this, but many of his actions are now preceded by a golden voiced narrator offering a suggestion of not only what he should do, but also a reaction to what he has actually done.

The Stanley Parable began as a free mod for Valve’s Half Life 2, and it wore that quite proudly, with deliberate references to the series in the form of wholesale reusing textures, assets and even entire map sections. It's still available to download for free, but this full game serves as an extension of the same idea, polished to a pristine shine with far better textures and level design, with some of the initial choices carried over and many new ones added.

Your earliest decision is to pick between two doors. The narrator suggests that you go left, doing so carries on the story without any hiccup until the next choice, disobeying means a brief attempt to get you back on track, but continuing to do so can lead to entirely unique outcomes.

Some of these branches are more extensive than others, some leading to elongated sections of unique gameplay, others offering further branching options. Though following the story as described by the narrator results in a narrative that is sewn up with a tidy bow, more interesting ideas emerge through different choices. The game starts to make huge statements about factors that weigh into modern game design like hand-holding, following a critical path without any player agency, extensive playtesting sessions, the issue of creating a game solely with the intent that it be enjoyed by an audience, along with scathing critiques of both overly pretentious art-first-design-later creation and unnecessary social integration.

A great deal of this feels clever, it avoids the common pitfall that games with a message about gaming fall into where their commentary on the ridiculousness of a trope is to simply repeat the trope and call attention to it, here each idea is taken to a ridiculous extreme, examined, then argued.

Though some playthroughs benefit from relying on continued repetition of the first few rooms, it can be tiresome wandering the same path hearing the same dialogue again in an attempt to reach the next ending. There’s no real way to combat this, the parts where this revisiting serves the narrative require it, but the sections which don’t unfortunately suffer for it.

MSI MPG Velox 100R Chassis Review

October 14 2021 | 15:04

Want to comment? Please log in.